Line Cord Resistors and

other Heater Droppers.

This page has come about mainly as a result

of having open circuit line cord resistors in eight out of my nine Meck

FM converters. This series of articles examines the options for modern

substitutes and other schemes for dropping the mains voltage for where

a series heater power supply is used. Where a transformerless power supply

is used for a radio or television set, the most efficient method of powering

the valve heaters is to connect them all in series, since the current through

the dropping device is a fraction of what it would be if the heaters were

in parallel. To this end, valves were designed specifically for this type

of operation. They have a controlled warm up time, so that individual valve

heaters are not overloaded during warm up, and the heaters are designed

for a specific current rather than voltage. European design favoured 100mA

and 200mA heater valves for radios, and 300mA for television. In the U.S.,

radios initially used a 300mA heater string, then 150mA. In most instances,

the 150mA valve voltages added up to around 120V, thus eliminating the

need for a dropper resistor. U.S. televisions initially used a 600mA heater

string, which was sometimes divided into two 300mA strings for part of

the circuit. 450mA was standardised later on.

In the early days, the series heater arrangement

came about to permit operation from DC mains, since transformer type power

supplies are suitable for AC only. However, the scheme remained in use

even when DC mains were no more. The main reason was that it eliminated

the heavy, bulky, and expensive power transformer. This convenience comes

at a disadvantage, with the internal circuitry, and usually also the chassis,

connected to one side of the mains, making it a shock hazard. Some apparatus

was better than others, in regard to avoiding a shock hazard to the user.

Methods for voltage dropping.

Where the sum of valve heater voltages

adds up to less than the mains voltage, the difference has to be dropped

by some means. Methods to do this include resistors, barretters, light

bulbs, or when the supply is AC only, capacitors, diodes, or transformers.

Resistive devices are cheap and popular, as well as functioning on both

AC or DC mains. They can be in the form of an ordinary wirewound resistor,

a barretter, light bulb, ballast tube, or a line cord resistor. The disadvantage

is that all the voltage dropped is converted to heat. 30W is not atypical

of the sort of dissipation. The overall power consumption is also higher

than if a power transformer was/could be used. When the mains is AC only,

other more efficient methods can be used. One well known method is to use

the reactance of a capacitor. The advantage here is no heat dissipated.

Another method, very popular in UK made television sets, is to use a silicon

diode, presenting a half wave current to the valve heaters. By using a

diode this way, the dissipation in the heater dropper resistor is reduced,

because the diode only conducts on every half cycle of the mains sine wave.

Of course a transformer can be used, which may be an auto transformer to

reduce bulk and expense, where isolation is not required.

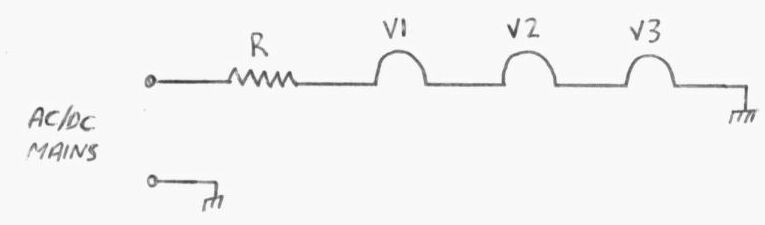

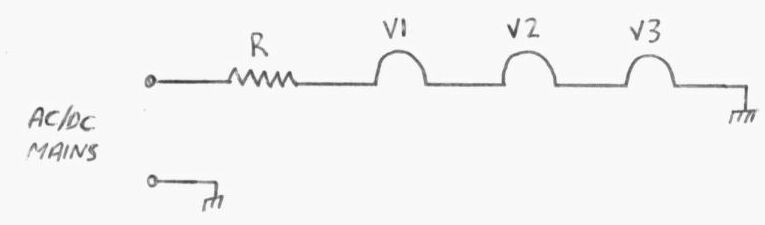

Part 1: Resistive droppers.

Here, R is any of the resistive devices

listed above. The value is found by ohms law where R=V/I. V is the sum

of valve heater voltages. For example, lets assume the set uses a 14F8,

12AT6, and 35W4 and is to operate from 120V mains. The sum of heater voltages

is 60.2. Now, the voltage to be dropped (V) is 120 - 60.2 = 59.8V.

The current consumption (I) is 150mA. So, R= 59.8/.15 or 399 ohms. The

power dissipated by this resistor is I^2*R. So, .15^2/399 = 8.98W.

Where an ordinary resistor is used and

it fails, it's easy enough to use a modern replacement, using resistors

in series or parallel to get the correct resistance, which is critical

and should not automatically be substituted with the nearest preferred

value.

Many circuits include a negative temperature

coefficient (NTC) thermistor in series with the dropper resistor. The purpose

of this is to remove the switch on surge current that occurs when the valve

heaters are cold. As current flows, the thermistor gradually warms up,

because of the voltage drop across it. The resistance then starts to fall

to a certain point, at which the full heater current flows.

Where a thermistor is not used,

it is worth noting that the lesser the value of dropper resistance, the

greater the switch on surge. It goes to reason, for example, that if the

dropper was 240 ohms, it would be impossible for more than 1A to flow with

a 240V supply. If, however, the dropper was only 120 ohms, then the surge

could be as high as 2A.

Big green resistor drops the mains voltage for the valve heaters.

Barretters were popular in Australian

and European AC/DC or DC only sets. These resemble a domestic light bulb,

but have an iron filament in a hydrogen atmosphere. Usually, they have

an E27 Edison screw or P base. Unlike a resistor or light bulb, they regulate

the current over a wide mains voltage. So, a typical set could run from

200-250V with no need to adjust anything. Also, the switch on surge is

reduced. It would be possible to use an ordinary light bulb and forego

the regulation feature as a replacement, but more than likely, it will

be necessary to provide a resistor as well, to get the correct heater current.

Barretters are fragile, and must be mounted away from speaker magnets,

since the iron filament will vibrate with the magnetic field and eventually

break.

Type 302 barretter is at the right.

Ballast tubes existed in some American

sets from around the 1930's and 40's. One kind is a wirewound resistor

assembled in what looks like a perforated metal valve, and has an ordinary

valve base. It may be possible to fit modern resistors inside the enclosure.

Even if not, they could be put elsewhere inside the set, above the chassis.

The other kind of ballast tube is in a glass envelope, and is really a

barretter under another name.

Light Bulbs can and have been used,

but resistance varies depending on the current flow, so it isn't practical

to calculate what wattage lamp is to be used, and what the associated resistor

(if required) will be. It will have to be done experimentally. As a starting

point, it is easy to determine what the current consumption of a light

bulb at its rated voltage is. P(power of lamp) = I(current) x V(voltage).

For example, a 240V 60W bulb draws about 250mA. A 75W 240V bulb would probably

be a good starting point for use in a set that had a 300mA heater string

(You have hoarded a lifetime supply of incandescent bulbs haven't you?

Because you won't be able to use a CFL or LED bulb in this application!).

Keep in mind that the resistance of a light bulb is much lower cold than

hot, so the switch on surge could be a problem. A thermistor could be of

use here.

Ordinary light bulbs have a tungsten filament,

so have the same temperature coefficient as a string of valve heaters.

Interestingly, a carbon filament bulb performs much like a negative coefficient

thermistor. This data was measured using two 240V 100W bulbs; one with

a tungsten filament, and the other with a carbon filament:

| Volts across bulb |

Carbon filament (mA) |

Tungsten filament (mA) |

| 40 |

45 |

155 |

| 80 |

110 |

230 |

| 115 |

170 |

270 |

| 140 |

235 |

310 |

| 180 |

320 |

360 |

| 215 |

395 |

390 |

| 240 |

415 |

420 |

| Cold resistance |

786 ohms |

40.6 ohms |

Characteristics of 240V 100W carbon and tungsten filament bulbs.

From this, one could deduce that the carbon

filament provides good inrush current protection, with such a high cold

resistance. However it does not provide current regulation like a barretter,

so is unsuitable for operating over a wide voltage range. As mains voltages

have been standardised for some time, this is not as important as it once

was. The tungsten lamp has less of a current variation over a certain voltage

range, but offers no surge protection at all. The effect of using a tungsten

lamp as a valve heater dropper is the same as if all the valve heaters

added up to the mains voltage. For example, if the mains voltage rises

10%, then each of the valve heater voltages rises by 10%.

In comparison, an ordinary wirewound resistor

does offer useful surge protection, but as the resistance does not vary

with current, the valve heaters will be subjected to a greater variation

in voltage than with a tungsten lamp dropper.

For these reasons it can be seen that

the barretter is actually the ideal type of resistive dropper.

40W light bulb used in the Operatic C64RC.

A domestic 240V 40W light bulb was used

in the Operatic C64RC as the dropper. Service notes indicate that it was

used due to barretters being in short supply. Because the bulb current

is too low on its own, it has a 2.5k resistor shunted across it. The next

size bulb up, 60W, passes too much current. The section of the heater string

comprising the 12SQ7,the 12SK7's, 50L6, and 35Z5 draws 150mA. Since the

6AN7 requires 230mA, the 150mA section is shunted by another 2.5k resistor.

Line cord resistors took over from

ballast tubes and other dropper resistors mounted inside radio cabinets,

and lasted until the 1950's when they fell from use. By then, a series

of valves had been developed for typical radio use which had 150mA heaters,

and when used together added up to around 122V, thus dispensing with the

need for any dropper for the U.S. mains supply. Line cord resistors were

not used with Australian sets due to their safety hazards, and were not

permitted by the authorities.

The reason for their popularity is that

they allowed midget sets to be constructed, as all the heater dropper heat

was dissipated outside the cabinet. Room was also not required inside the

set for the large resistor or ballast tube.

A line cord resistor looks like an ordinary

cloth covered appliance cord, but closer examination reveals three conductors.

There are two ordinary conductors, one for (what is hopefully) the neutral,

the other to feed the rectifier plate with the mains voltage. The third

conductor is actually resistance wire wound around the length of the cord

and provides the heater voltage. Needless to say, shortening this kind

of cord will subject the heaters to excessive voltage. Provided the cord

is left stretched out, it dissipates the heat effectively. If left coiled

up, it could be a fire hazard.

The insulation around the resistance wire

is unreliable making them a shock hazard. Also, the resistance wire is

not as flexible as the ordinary conductors. So, continual rolling up or

moving the cord will eventually cause it to break. It's the usual cause

of no heaters lighting in a set fitted with one.

Construction of a line cord resistor. The red and black conductors

connect to the mains plug and thus provide full voltage to the B+ rectifier.

Wound around the black conductor can be seen the nichrome resistance wire

for dropping the voltage for the valve heaters. With nothing but

a woven cotton outer covering, the shock hazard is obvious.

And so to the Line Cord Resistor

Replacement:

Line cord resistors have not been made

for many years, and with today's regulations, probably never will be again.

Faced with an open circuit line cord, many restorers have resorted to other

types of dropper, which apart from detracting from originality, can present

its own challenges. Replacing a line cord with an ordinary resistor is

often not practical because the set's cabinet is too small to accomodate

it, and the resulting heat dissipation will cause damage. Sometimes the

resistor has been installed in an external metal box, which obviously stands

out like the proverbial.

Some restorers use capacitive droppers

which have the advantage of no heat dissipation, and provided there is

enough room in the cabinet are a practical alternative. However, many restorers

make the error of simply calculating the capacitor value by the equivalent

reactance, which overloads the valve heaters. There are limitiations of

this type of dropper which need to be understood before choosing it. The

details of how to design a capacitive dropper circuit are covered in Part

2.

Diode droppers also take up little space,

but for most applications a dropper resistor is still required. Nevertheless,

the size of resistor and its heat dissipation is a lot less than a resistor

on its own. Again, the calculations are often done in error, assuming the

voltage is simply halved, with the valves being overloaded. The details

are covered in Part

3.

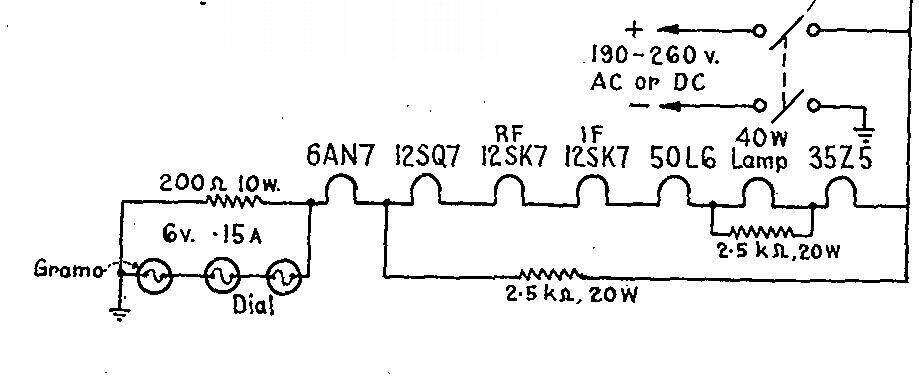

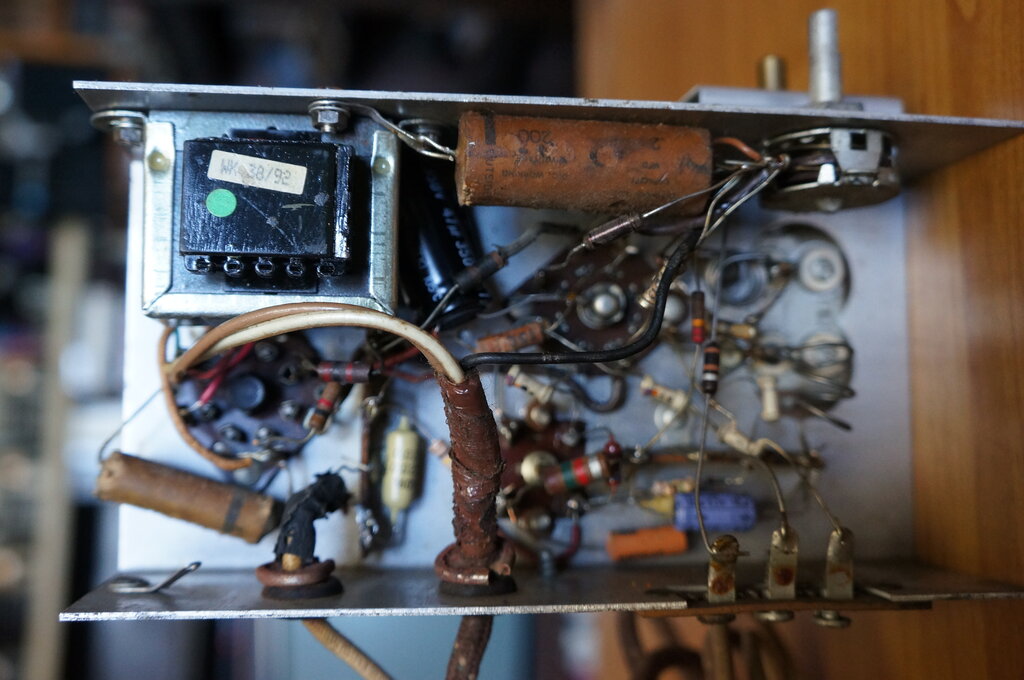

A transformer in an external box is another

option, but again looks out of place. Once in a while, there is just enough

room to install a small heater transformer inside the set, as was done

with this Meck FM converter.

Since only 12.6V at 300mA was required, there was enough room to

fit this heater transformer in a Meck FM converter.

However, it occurred to me that it should

be possible to make a replacement using wire from an electric blanket heating

element. This has the required insulation (in fact, much better than what

was originally used), and flexibility requirements (again, vastly improved

on the original). By shrouding it in hollow shoe lace along with two ordinary

conductors, it should therefore be possible to make an authentic replacement.

Indeed, it turned out that electric blanket element wire also had the right

electrical characteristics, and the idea has been successfully implemented

on two receivers so far.

Reproduction line cord resistor made for an Emerson CF255.

Thus, there is no need to butcher the original

radio with non original droppers.

The first reproduction line cord resistor

was used on one of my Meck FM converters. See

the full description here.

The second was made for one of my Emerson

CF255's. This set requires a tap for the dial lamp, but this was easily

provided.

Transformers.

No introduction needed here. Efficiency

is high, and there's no asymmetrical loading of the mains or reducing the

power factor. Not frequency critical within limits either. As we're talking

about live chassis sets here, an auto transformer can also be used. Obviously,

a transformer is the best way to power the heaters when practical. Of course,

transformers are suitable only for AC supplies.

Using droppers for other loads.

For purely resistive loads, like light

bulbs, brush motors or heating elements, any of the droppers described

will work. However, with the exception of using a transformer, all the

droppers will give higher voltage on no load, so are only suitable for

constant loads.

For inductive loads like small shaded

pole induction motors, anything but the diode dropper will work. The capacitive

dropper will work, but the calculations are not the same. Suffice to say,

it's easiest to use trial and error. I had to replace the fan motor in

one of my fan heaters. As it happened I had U.S made motor that fitted

perfectly. However, I had to drop 120V to use it on the local 240V supply.

I used a 2.8uF 440VAC capacitor in series

which worked perfectly. Note that because of resonance effects, the voltage

across the capacitor may be much higher than the mains supply. This is

why motor run capacitors are 440V and not 250VAC.

Home